“In his vastness and mobility, Chesterton continues to elude definition: He was a Catholic convert and an oracular man of letters, a pneumatic cultural presence, an aphorist with the production rate of a pulp novelist. Poetry, criticism, fiction, biography, columns, public debate...Chesterton was a journalist; he was a metaphysician. He was a reactionary; he was a radical. He was a modernist, acutely alive to the rupture in consciousness that produced Eliot's "The Hollow Men"; he was an anti-modernist...a parochial Englishman and a post-Victorian gasbag; he was a mystic wedded to eternity. All of these cheerfully contradictory things are true … for the final, resolving fact that he was a genius. Touched once by the live wire of his thought, you don't forget it ... His prose ... [is] supremely entertaining, the stately outlines of an older, heavier rhetoric punctually convulsed by what he once called (in reference to the Book of Job) "earthquake irony". He fulminates wittily; he cracks jokes like thunder. His message, a steady illumination beaming and clanging through every lens and facet of his creativity, was really very straightforward: get on your knees, modern man, and praise God.”

James Parker, A Most Unlikely Saint, The Atlantic, April 2015.

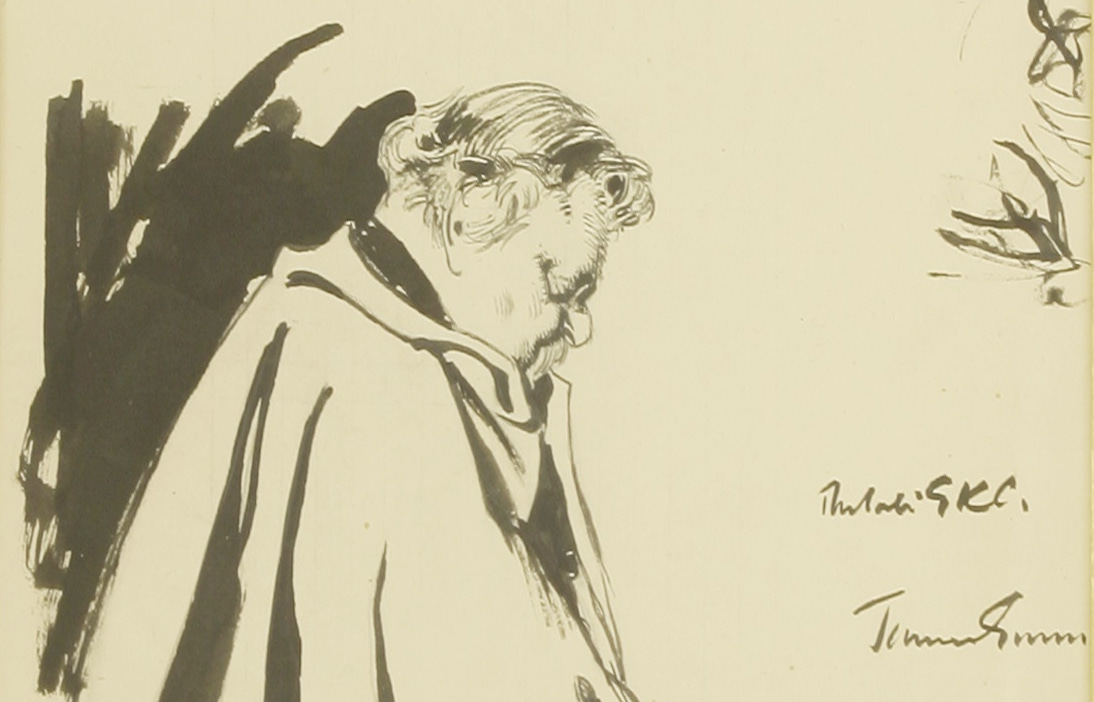

I’m here to introduce you, or perhaps re-introduce you, to a writer of enormous girth and importance.1 His full name is Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874-1936), although he is usually known by the name printed on the covers of his books: GK Chesterton. Sometimes he’s just GKC. From this magnificent thinker, we can learn how to think forwards (and sideways) rather than, as most people nowadays do, backwards (and upside-down).

Although he is most well known today for his detective stories about the amateur detective Father Brown, a character whose literary life has been translated many times for radio, film, and television, Chesterton’s main writings are non-fictional. His work covers multiple genres and a bewildering range of subjects. By the usual estimates, he wrote around 9000 essays and around a hundred books, including books of poetry. He was forever writing—and often doodling—on things.

Here’s a story about this. As a young journalist, he lived at the top of a block of flats in the London Suburb of Battersea that didn’t have a working elevator. So Chesterton would start writing an article at the bottom of the stairs and finish the article by the time he got to his apartment at the top. He had to take breaks in between to catch his breath, of course, because he was, for his entire adult life, never in good shape.

As this shows, he wrote while on the go. And he was always thinking forwards. Understanding what this means requires that we also get a feel for what it means to think backwards. Here’s GKC, in his essay, The Man Who Thinks Backwards:

“The man who thinks backwards is a very powerful person to-day: indeed, if he is not omnipotent, he is at least omnipresent. It is he who writes nearly all the learned books and articles, especially of the scientific or skeptical sort; all the articles on Eugenics and Social Evolution and Prison Reform and the Higher Criticism and all the rest of it.”

Before I lose you, keep in mind that this is from an essay in a collection published in 1912 under the title, A Miscellany of Men, so let’s take a moment to consider what this backwards-thinking person would look like today. This shouldn’t be too difficult since we live in a time in which thinking backwards is the norm. The backwards-thinking man would be, above all else, very fashionable. He’d support the Current Thing. He’d be a Davos Alibi Bot like Yuval Harari or a censorship supporter like Malcolm Gladwell. He’d have bestselling books that deserve to be burned, not for some childish reason like censorship but for simply being more valuable to people as fuel for fire than as fuel for thought. The backwards-thinking man would be progressive and politically correct, and, as Chesterton says, he might even be “a woman.” Nowadays, the man who thinks backwards may even be a man who thinks he is a woman.

Chesterton doesn’t define thinking backwards precisely but shows us what it looks like by contrasting it with thinking forwards. He considers a simple object: a fire poker. He looks at the fire poker forwards, then backwards. Looking at it forwards would mean endlessly returning to first principles and causes. So Chesterton looks at man as the inventor of the fire poker. With this in mind, and without forgetting the fire-poker, let’s take a brief detour (a sideways glance) at what Chesterton thinks about this creature called man:

“The simplest truth about man[, he says,] is that he is a very strange being; almost in the sense of being a stranger on the earth. In all sobriety, [man] has much more of the external appearance of one bringing alien habits from another land than of a mere growth of this one. He cannot sleep in his own skin; he cannot trust his own instincts. He is at once a creator moving miraculous hands and fingers and a kind of cripple. He is wrapped in artificial bandages called clothes; he is propped on artificial crutches called furniture. His mind has the same doubtful liberties and the same wild limitations. Alone among the animals, he is shaken with the beautiful madness called laughter; as if he had caught sight of some secret in the very shape of the universe hidden from the universe itself. Alone among the animals he feels the need of averting his thought from the root realities of his own bodily being; of hiding them as in the presence of some higher possibility which creates the mystery of shame.”

Now, let’s get back to the connection between this strange creature, who laughs and feels shame, and the fire poker. Man is so naturally naked and vulnerable that he “has to go outside himself for everything that he wants.” If he wants to cook or stay warm, he needs heat. So he makes a fire. But he discovers, soon enough, that the fire is hot—too hot for fingers. He finds that he needs a way to manage the fire. So he invents a fire poker. Thinking about the fire poker in this way, i.e. forwards, helps us to recognise that it is a tool for managing fires and not a weapon to use in lectures against students who are being especially stupid.

But if this is thinking forwards, what is thinking backwards? I’ll quote Chesterton at length on this:

“Now our modern discussions about everything, Imperialism, Socialism, or Votes for Women, are all entangled in an opposite train of thought, which runs as follows:—A modern intellectual comes in and sees a poker. He is a positivist; he will not begin with any dogmas about the nature of man, or any day-dreams about the mystery of fire. He will begin with what he can see, the poker; and the first thing he sees about the poker is that it is crooked. He says, ‘Poor poker; it’s crooked.’ Then he asks how it came to be crooked; and is told that there is a thing in the world (with which his temperament has hitherto left him unacquainted)—a thing called fire. He points out, very kindly and clearly, how silly it is of people, if they want a straight poker, to put it into a chemical combustion which will very probably heat and warp it. ‘Let us abolish fire,’ he says, ‘and then we shall have perfectly straight pokers. Why should you want a fire at all?’ [The people around him] explain to him that a creature called Man wants a fire, because he has no fur or feathers. He gazes dreamily at the embers for a few seconds, and then shakes his head. ‘I doubt if such an animal is worth preserving,’ he says. ‘... you had better abolish Man.’ At this point, as a rule, the crowd is convinced; it heaves up all its clubs and axes, and abolishes him. At least, one of him.

In summary, thinking forwards is about looking for the right contexts and principles according to which we can understand things in the best way. To appreciate Chesterton, it helps to recognise that this was always his mission: to return to origins. No wonder he was so original. Whether he was talking about what he found in his pockets (which he never did completely because he said “the age of great epics is over”) or the best way of catching a train (which for him was to be late for the one before), he was always thinking about principles and causes, about the roots of things and not just the branches. Thinking backwards would be the opposite of this. Thinking backwards means thinking badly. It means trying to escape and abolish reality. And there is, as you know, plenty of such thinking going around.

As the above suggests, Chesterton was a kind of idealist. That’s a dangerous label to apply to him, given its many misleading connotations. For clarity’s sake, we should therefore remember that, for him, idealism means “considering everything in its practical essence. Idealism only means that we should consider a poker in reference to poking before we discuss its suitability for wife-beating.” In his 1910 book What’s Wrong With the World, which I’ve just quoted from, he explains his starting point. If you want to know what’s gone wrong in the world, you don’t need the practical man but the “unpractical” man. You need a theorist who has some theory of what is right. “When things will not work, you must have the thinker, the man who has some doctrine about why they work at all.” For instance, you need a clear picture of health before you try to cure a disease, otherwise, you’re likely to make the common medical mistake of solving problems by making them worse. If you want to solve disorder, you need a clear sense of what order looks like. If you don’t want to misjudge a thing, you need to know what it means to judge it rightly.

Chesterton was vehemently against what he called the “negative spirit.” The negative spirit means criticising something without having any solid idea of what would be better. It runs on instinct but not on intellect. Here’s what Chesterton has to say about the negative spirit in his 1905 book Heretics:

“Every one of the popular modern phrases and ideals is a dodge in order to shirk the problem of what is good. We are fond of talking about ‘liberty’; that, as we talk of it, is a dodge to avoid discussing what is good. We are fond of talking about ‘progress’; that is a dodge to avoid discussing what is good. We are fond of talking about ‘education’; that is a dodge to avoid discussing what is good. The modern man says, ‘Let us leave all these arbitrary standards and embrace liberty.’ This is, logically rendered, ‘Let us not decide what is good, but let it be considered good not to decide it.’ He says, ‘Away with your old moral formulae; I am for progress.’ This, logically stated, means, ‘Let us not settle what is good; but let us settle whether we are getting more of it.’ He says, ‘Neither in religion nor morality, my friend, lie the hopes of the race, but in education.’ This, clearly expressed, means, ‘We cannot decide what is good, but let us give it to our children.’”

In the Daily News (published on the 7th of July, 1906), Chesterton wrote: “I have always engaged, and always shall engage, in any sort of discussion on the first principles of human existence.” Although Chesterton was a journalist, this shows us that his aims were profoundly philosophical, often theological. He was Plato of the Pen, the Aristotle of the London Omnibus; he was a pub-crawling Aquinas. “We should thank God for beer and Burgundy by not drinking too much of them,” he reminds us. I’d say that Chesterton was a metaphysical journalist engaged in journalistic metaphysics, which is very different from a great deal of journalism today which isn’t even journalistic journalism.

Chesterton’s interest in recovering principles and causes was not about showing off philosophical abstractions. His point of departure was simple. He noticed that “the world is in a permanent danger of being misjudged.” The world, this very environment that we are immersed in, is in a permanent danger of being overlooked and forgotten. In Chesterton’s case, this was often quite literal; it was a common feature of his everyday experience.

Here’s another story that places this in perspective. On various occasions, he’d send a telegram to his wife Frances from an incorrect location, writing such things as: “Am in Market Harborough. Where ought I to be?” To this, Frances would reply, “Home.” Another story of a different kind reveals Chesterton’s quirky obliviousness to the world around him. At the Chesterton conference I attended in London two years ago, the then 100-year-old Aidan Mackey (who has since passed away), one of the great curators of the Chesterton Collection, told a story about GKC that I don’t think has ever appeared in print. Mackey heard the story directly from Dorothy Collins, who was Chesterton’s secretary and adopted daughter. Chesterton used to travel around a lot but was never good at packing. Things of such a practical nature were beyond him—and I can relate—so Frances did the packing. When he returned after a night away, Frances apologised profusely for forgetting to pack his pyjamas. “Did you buy some to replace the missing pyjamas?” she asked him. “Buy some?!” said Gilbert in perplexity. “I didn’t know you can buy pyjamas!”

Chesterton has this lovely idea to explain something about the human experience (see The Illustrated London News, 2 April 1932). He says we often go about with heads like wastepaper baskets. The ideas we think we have discarded, we have, in reality, just thrown back into our heads. You’ll hear the most convinced relativist declaring that there is no truth and that morality is arbitrary and then, a moment later, you’ll hear him declare, “We have problems to solve! Something must be done!” That’s what it means to have a head like a wastepaper basket and in one way or another, all of us have something of this experience. We take for granted what we should take as a gift. Here’s Chesterton in his first book of essays, The Defendant (1901):

“I have investigated the dust-heaps of humanity, and found a treasure in all of them. I have found that humanity is not incidentally engaged, but eternally and systematically engaged, in throwing gold into the gutter and diamonds into the sea. I have found that every man is disposed to call the green leaf of the tree a little less green than it is, and the snow of Christmas a little less white than it is; therefore I have imagined that the main business of a man, however humble, is defence. I have conceived that a defendant is chiefly required when worldlings despise the world—that a counsel for the defence would not have been out of place in that terrible day when the sun was darkened over Calvary and Man was rejected of men.”

We should not “look a gift universe in the mouth,” says Chesterton. But we do, sadly. This is the great tragedy of our race, made worse, probably, because of the various trappings of the age in which we live. In general, we will overlook an actual paradise just to have a bite of one little piece of fruit from the one tree we shouldn’t eat from. As Chesterton says, we don’t just “incidentally” despise the many treasures we are given; we find ways to do it “eternally and systematically.” This has happened throughout human history, even if the most recent forms of it might take on new names like decolonisation, fourth-wave feminism, the fourth industrial revolution, and AI. The irony of modern ideologies and technologies is that they are parasites: they depend on the very things they attack.

If we are to avoid being mere parasites, we need to look at things differently than most other people do. We have to find a way to respond to the world in gratitude and wonder, and Chesterton shows us the way. His whole life was a pursuit of the deepest truths and the most exuberant joys. Here’s something else he said that resonates with this, from his book Tremendous Trifles (1909):

“Everything is in an attitude of mind; and at this moment I am in a comfortable attitude. I will sit still and let the marvels and the adventures settle on me like flies. There are plenty of them, I assure you. The world will never starve for want of wonders; but only for want of wonder.”

Chesterton defends things that most others take for granted. What does he defend? He defends human dignity, the family, localism, private property, and patriotism. He defends the metaphysical and biological differences between men and women. He defends democracy, although what he understands by democracy is different from what most people think of as democracy today. Democracy, for him, is not voting for the party you dislike the least, but actively participating in politics, especially local politics. He writes, “What we should try to do is make politics as local as possible. Keep the politicians near enough to kick them.” It is not about handing power to self-interested demagogues but about taking responsibility for your part in the health of society. He also defends the Christian faith and is recognised today as a significant Christian apologist.

To sane people, who want to think forwards, nothing here should kick up too much of a fuss. But everywhere Chesterton wrote or spoke in defence of common, ordinary things, the world around him went mad. And so Chesterton was known, even in his own time, as a controversialist. He was controversial, not because he said outlandish things but simply because he wanted to tell the truth. He predicted, mind you, the great battle for the truth that is now raging in our own time. He said that when unanimity is turned into an “absurd assumption ... a man may be howled down for saying that two and two make four” and persecuted for “calling a triangle a three-sided figure” and hanged “for maddening a mob with the news that grass is green.” (The Illustrated London News, 14 August 1926).2

The earliest controversy that made a name for him as a controversialist relates to our own history and context. During the South African War, Chesterton was a pro-Boer, against the British establishment. His political views were very much inspired by the self-sufficiency of the Boers. He was deeply impressed by how Afrikaners looked out for their own and by their loyalty to people and not mere abstractions.3

Not too long after earning a name as a controversialist for being a pro-Boer, Chesterton got into another controversy with the atheist Robert Blatchford, and in the process made it known that he was a Christian. C. S. Lewis said that Chesterton’s 1925 book The Everlasting Man contributed enormously to his conversion to Christianity. He called it “the best popular apologetic I know.” The book was also cited in Lewis’s list of 10 books that “most shaped his vocational attitude and philosophy of life.” I should probably mention, having said this, that getting as deeply into Chesterton as I have may remove any good reasons you might have had against converting to Catholicism.

So, yes, Chesterton was forever fighting. But, as I’ve said, he was always fighting to defend; he refused to give in to the negative spirit and embodied a properly positive spirit. One of the tricks of the current backwards-thinking people is that they have seemingly positive aims: diversity, equity, and inclusion, for example. But you realise quickly that these are simply new manifestations of the same old negative spirit. A process is named, not an aim. As a result, the things we ought to cherish are hurled into the rubbish dump or something worse than a rubbish dump, namely an empty head. No wonder schools are becoming places where kids learn how to be stupid and Universities are becoming monuments to incompetence.

There are many reasons to despair, and you might think that Chesterton, by fighting against so many destructive ideas and forces, would get overwhelmed by being in what sociologists call a cognitive minority. But you will find no trace of despair in Chesterton’s work. GKC was three inches taller than I am and weighed about double what I do and yet he was, in a way, much lighter than I am. He wrote this in my favourite book of all time, Orthodoxy (1908):

“Seriousness is not a virtue. It would be a heresy, but a much more sensible heresy, to say that seriousness is a vice. It is really a natural trend or lapse into taking one’s self gravely, because it is the easiest thing to do. It is much easier to write a good Times leading article than a good joke in Punch. For solemnity flows out of men naturally; but laughter is a leap. It is easy to be heavy: hard to be light. Satan fell by the force of gravity.”

Chesterton was always laughing while he was fighting—as if the core fight, the real heart of the battle, was always to fight for joy, to make sure that wonder was not lost in the heat of the fray. After one debate, Cosmo Hamilton, his opponent, had this to say about him:

To hear Chesterton’s howl of joy … to see him double himself up in agony of laughter at my personal insults, to watch the effects of his sportsmanship on a shocked audience who were won to mirth by his intense and pea-hen-like quarks of joy was a sight and sound for the gods … it was monstrous, gigantic, amazing, deadly, delicious. Nothing like it has ever been done before or will ever be seen, heard and felt like it again.

It is on this note, however, that I want to shift the focus a bit. We have thought forwards about Chesterton and arrived at his principles—his defence of eternal truths and present treasures. I’ve given you a sense of the joyful heart behind his philosophy. But I also want to briefly touch on thinking sideways before I end. Much of Chesterton’s constant return to principles and causes allowed a certain expansiveness and flexibility of thought. He was able to see truth as deep and paradoxical, rather than as something that ought to be reduced to mere facts, as tends to happen today in this age of information and data-mining.

In his book The Club of Queer Trades, which indirectly inspired the still brilliant David Fincher movie The Game (1997), one of the characters, Basil Grant, has this tirade against “facts” for pointing in all directions “like the twigs on a tree.” What counts is the truth, which is the life of the tree that unifies all of those facts. And truth isn’t just univocal, like facts, but evocative, mysterious, and poetic. Truth was and is primarily analogical because it is rooted in the analogy of being, as discussed by the great Catholic philosopher St. Thomas Aquinas.

After Chesterton died, his friend Hillaire Belloc wrote a little book called On the Place of Gilbert Chesterton in English Letters (1940). When asked what Chesterton’s legacy was, Belloc took the time to name a few things that made his writing especially remarkable. I just want to focus on one of them. Here’s Belloc:

“[P]arallelism was the weapon peculiar to Chesterton’s genius. His unique, his capital, genius for illustration by parallel, by example, is his peculiar mark. The word ‘peculiar’ is here the operative word. Many have precision, though few have his degree of precision. Multitudes, of course, are national in various ways. But [n]o one [else] whatsoever that I can recall in the whole course of English letters had his amazing—I would say superhuman—capacity for parallelism.”

Belloc defines parallelism further: “Parallelism consists in the illustration of some unperceived truth by its exact consonance with the reflection of a truth already known and perceived.” There’s a lot that can be said just about this, like, say, how it is at the root of all poetry, as well as how it inspires humour. But as I close I want to return to just one specific example of parallelism: the image of the fire poker that Chesterton uses when discussing thinking forwards and backwards. While he argues for the best way to understand the fire poker, he comes up with a particularly apt analogy, which I deliberately left out earlier so that I can discuss it here as I close. Chesterton suggests that the fire is like faith, like goodness itself, and the fire poker is like the priest. And by this suggestion, he notes that human beings always need mediators. We need go-betweens. Our success and happiness are owed to having the right mediators for the things we are trying to live with. When we want to discuss ideas, language is the mediator we need. When we want to nourish our bodies, we turn from good words to good food. When we want to worship God, we go to church. And when we want to fight legal battles, lawyers are the right mediators for the job.

I could go on multiplying parallels but the point I want to end with is simply this: when it comes to finding sanity and sense, joy and wonder, especially now in this time of a global crisis of meaning, I have found Chesterton to be one of the best mediators available. He is a trustworthy, funny, profound companion and a guide. He is a bridge to what is best. If you have not read him yet, I’d suggest that now would be a good time to start. If you have read him, thankfully, you still haven’t read everything he wrote. There is absolutely no shortage of Chesterton. The world will never want of wonders and so it’s is good to also know that the want of Chesterton is easy to address.

This is a written version of a talk I gave recently in Tulbagh, South Africa, a bit different from the talk I presented last year. I am, once again, very grateful to Russell Lamberti and Piet Le Roux for the opportunity to share my thoughts. The topic was apt. For those who don’t know, you can get hold of one of my books on Chesterton’s thinking, published by Cascade in 2016, called Seeing Things as They Are: G. K. Chesterton and the Drama of Meaning.

In my forthcoming book on Chesterton, The Roots of the World: The Remarkable Prescience of G. K. Chesterton (Cascade, 2025), I tackle how that jolly journalist was able to see so much of the future that is now our present. I’ll say more about this here in future, when the time is right.

Here’s something he said that fits this vision of the world: “Cosmopolitanism gives us one country, and it is good; nationalism gives us a hundred countries, and every one of them is the best. Cosmopolitanism offers a positive, patriotism a chorus of superlatives. Patriotism begins the praise of the world at the nearest thing, instead of beginning it at the most distant, and thus it ensures what is, perhaps, the most essential of all earthly considerations, that nothing upon earth shall go without its due appreciation. Wherever there is a strangely-shaped mountain upon some lonely island, wherever there is a nameless kind of fruit growing in some obscure forest, patriotism ensures that this shall not go into darkness without being remembered in a song.”