I don’t think it’s possible to properly understand the contemporary world, especially the world of media messaging and politics, apart from an old idea hidden in plain sight in a common word: scandal. Because many aren’t aware of certain subtleties behind this idea, they find themselves ensnared when they could be free. I thought I’d write this as an act of gentle exorcism. Demons are often cast out when we simply speak the truth.

Of course, we all have a fairly intuitive sense of what a scandal is. A high-profile figure commits adultery. An actress undergoes body-modification surgery and self-identifies as a man. A rapper stands trial for sexual assault, racketeering, and sex trafficking. Not knowing someone is filming, the wife of a French politician shoves her husband in the face. A controversy-monger known for his ability to alienate everyone around him releases a song called Heil, Hitler. A great deal of mainstream journalism is scandalising, and so is gossip. Scandals make for excellent clickbait. They lure and ensnare.

However, the above are only the most obvious examples of scandals. Less obvious would be the case of a cheesy pop song that is so bad that everyone shares it only to deride it, with the unintended consequence that the song goes viral. A car accident that causes traffic in the opposite lane to slow down is scandalous because people want to look closer, even while something in them wants to look away. Sometimes, the scandal is just an absurd branding campaign that fails to land or the latest AI video that claims to be real. Even doomscrolling in search of scandals is scandalous.

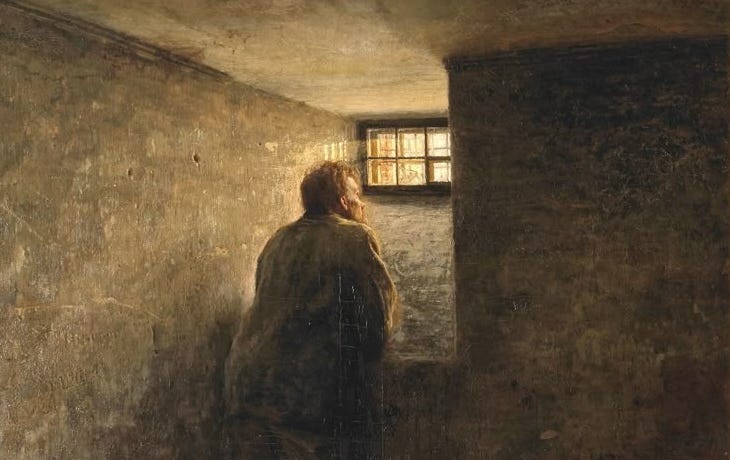

The word scandal is, in fact, ancient. Its earliest form is the Greek word skandálon, which is found in Homer and other pre-classical sources. Where it doesn’t indicate the whole trap, it refers to the bait-stick or trigger of a trap that, when disturbed, ensnares an animal. This bait-and-trap structure helps get us closer to the meaning of the idea for us today. Such a trap is inherently deceptive, as well as being dangerous. It takes more than it gives. An innocuous appearance is capable of causing terrible ruin. The skandálon alters the course of the unsuspecting animal, which feels free as it moves to snatch up an easy meal, hoping to walk away unscathed. Unfortunately, it stops dead as the trigger is released and the trap closes.

The word scandal has come to us mainly via the Bible’s New Testament, and it is also in the biblical text that we gain many insights into how to avoid being trapped by scandals. The noun skandálon appears 15 times across 13 verses, and the verb skandalizō appears 29 times across 27 verses. English translations of the idea—as stumbling block, sin, or obstacle—aren’t wrong. But they somewhat miss the deeper meaning at play in that word. To appreciate that deeper meaning, let’s look at a sequence of events in the sixteenth chapter of St. Matthew’s gospel.

At one point, Jesus, having become rather famous, asks his disciples who they think he is. They initially respond by reporting what their equivalent of mainstream media says: “Some say John the Baptist; others, Elijah; still others, Jeremiah or one of the prophets.” Jesus doesn’t care what uninquisitive journalists are saying, so he gets more personal. “I’m interested in who you say I am.” Peter answers: “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God.” Jesus praises Peter for grasping what Fake News doesn’t: “And I also say to you that you are Peter (Petros), and on this rock (petra) I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not overpower it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth will have been bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will have been loosed in heaven.”

After this, things take a dark turn as Jesus tells his disciples what being the Messiah means. He’s not expecting to be treated well. He explains that it will be “necessary for him to go to Jerusalem and suffer many things from the elders, chief priests, and scribes.” He will be killed, he says, and raised on the third day. Peter, understandably, doesn’t get the bit about the third day. It’s the bit about suffering and death he latches onto, and he’s horrified. “Oh no, Lord!” he says. “This will never happen to you!” Jesus has some strong words for Peter, the very same Peter he has just praised: “Get behind me, Satan! You are a skandálon to me because you’re not thinking about God’s concerns but human concerns.”

In the narrative trajectory of this passage, we gain a great deal of insight into what sort of trap a skandálon is. The story starts with an increasing disclosure of reality, which beautifully builds in a crescendo. First, we have a tentative gesture towards disclosure, the Fake News, which opts for political correctness over truth. Second, we have a bold unveiling in Peter’s declaration. Third is an affirmation of that declaration by Jesus. And fourth, we find Jesus telling his disciples something about what it means to live in the reality of that unveiling—I’m referring to Jesus’ pronouncement about having keys to the kingdom, which implies having the ability to unlock access to an entirely new way of being. But right towards the pinnacle of the crescendo, a dissonant chord is struck, and Peter doesn’t like it. He hates it so much he fails to hear the dissonance resolve, albeit ever so gently, at the first announcement of the resurrection of the Son of God. That’s when Jesus interrupts the music and tells Peter he’s taken up Satan’s cause, not his own.

This is significant because, as we understand from this historical-social context, Jesus is Peter’s rabbi—his teacher. The entire rabbinic tradition involved apprenticeship. Rabbis chose disciples whom they saw as capable of emulating them. If a rabbi ate a certain way, that’s how his disciples would eat. If the rabbi prayed a certain way, his disciples prayed as he did. If he washed his hands a certain way, that’s how his disciples washed their hands. When a rabbi called disciples, he was implicitly saying, “I believe you can be like me.”

If you jump a few chapters back, to Matthew 14, you’ll read about how Jesus’ disciples are fishing on a lake. Much to their astonishment, they see Jesus walking on the water towards them. They are initially terrified and mistake him for a ghostly apparition until Jesus calls out to them. “Take courage,” he says. “It is I.” Immediately, Peter asks Jesus to command him to join him out on the water. The whole episode is already strange enough, so why does Peter do this? Yes, walking on water would be pretty nifty, but within this world, the main cause for his enthusiasm would be that it was in the very nature of a disciple to do whatever his teacher was doing. That was the whole point. If your rabbi enjoyed taking walks on lakes, then you’d be up for doing exactly that.

But, back to Matthew 16, when Jesus reprimands Peter and calls him Satan, he implies that Peter has opted to emulate an entirely different teacher, namely, the chief spiritual force of opposition and accusation. Peter is acting as a scandal to Jesus by trying to cause him to step away from his mission. Peter wants to act as a mediator of Jesus’ desires, when it is his job to align himself with Jesus’ desires. And it is in this that we get to the core of what scandals are about. The issue is mediation.

We are usually oblivious to mediation, even while it pervades our entire consciousness and shapes our every motivation and action. We easily perceive things but we do not so easily realise that nothing appears to us without mediation. We give epistemological priority to the visible, even though the invisible is ontologically supreme. Our consciousness grasps nothing apart from a mode of anticipation acquired vicariously—a pre-organised and pre-articulated mental relationship moulded to a remarkable degree by external sources. The ancients were much more aware of this. They gave different names to such external sources, calling them angelic, daemonic, demonic, and the like. We moderns are less aware of such imposing forces but we try to make up for abandoning the much more evocative and efficacious language of the ancients by using modern notions that lack poetic clout; words like ‘Zeitgeist’ and ‘patriarchy’ and ‘woke mind virus’ and ‘the media’ and ‘leftism’—but such terms are only ways of noting, often without sufficient precision and without alerting us to how we have copied our views from elsewhere, that more mediation is at work than is obvious to us.

We can moderate such mediation. But this is only to say that all mediation, which is by its very nature intermediation, also includes self-mediation. There is also no escaping that we, on our own, are not the only ones interpreting phenomena. What this has to do with scandals, I’ll get to in a moment, but suffice it to say for now that while the animal is looking at the bait in the trap, he is not only not looking at the trap, he is also not looking at the one who put the bait and the trap there in the first place. He is not looking at the hunter. Jesus alerts us to the presence of the hunter by pointing out not only that Peter is wrong but by pointing out who Peter is emulating.

As René Girard’s work emphasises, others are the primary mediators of our desires. Human autonomy is bunk. What we want is shaped by what others want. In a certain sense, of course, when Jesus is telling his disciples about what is to happen to him, he does not want to suffer and die at the hands of malevolent torturers and murderers. Rather, he wants to do the will of the Father, and the natural consequence of that obedience is to be treated poorly by people in the grip of evil. Above all else, it is the desire for God and for God’s rule and reign to be manifest on earth as it is in heaven that Jesus models for his disciples. It is this way of desiring that he wants Peter to emulate.

Peter’s immediate reaction, however, is to mistakenly assert the priority of the visible over the invisible. Stupidly and naively, he asserts that self-mediation ought to be more potent and more important than intermediation, even though it is less in tune with reality. This reframes perception as a domain of rivalries by implicitly offering a command: ‘Don’t look beyond the immediately obvious!’ Peter sees only pain and death. He fails to heed the paradox that Jesus has uttered. The end of the road is not the end of the road but its beginning.

“If your eye scandalises you, tear it out,” says Jesus in Matthew 5:29 and 18:9. The meaning of this becomes clearer in the light of what I’ve said above. It is certainly a hyperbolic statement, not to be taken literally. But its point is not merely about taking radical measures to avoid sin, as the usual translations tend to imply. It is about de-scandalising perception. That’s how I read the bit about tearing your eye out. If your very mode of perception draws you into the clutches of a hunter, you need a new way of perceiving. On the one hand, yes, this must involve something like a total overhaul of our scandalising attention to the world. More practically, however, it involves emulating the unscandalised and unscandalisable.

When we look at common scandals, overt and covert ones, we see a pattern. They want us to stay within the realm of rivalrous emulation. Once you know this, it doesn’t take too much effort to identify the models of our rivalrous desires. Just spot whose ego is inflated as others are crushed, defamed, deligitimised, and sidelined. Remember: scandals take more than they give. Often, scandals thrive on a hidden rivalry with those who are supposedly in the know. This is why doomscrolling is scandalous. We are not allured by what we see, at least not only. Merely mechanical causes like videos and pictures and words don’t account for why we find ourselves glued to our screens. Rather, such attention to so much drivel is driven by an implicit sense we have that, if we stop scrolling, others will be in the know while we remain ignorant. It is the mediation that matters, not the message.

De-scandalising requires observing the potential and/or implicit rivalry between ourselves and those mediating our perceptions for us, and it especially means noticing that this rivalry stands in the way of our coming into contact with reality. The rival wants to be more real than reality. In contrast, a trustworthy model wants to usher us into a deeper sense of reality. What is needed, as an antidote, is a mediator who is also an ally—a mediator who wants you to be free, not ensnared; who helps you to transcend your appetites; whose desire will grant a deepening of attention to what matters; a mediator whose presence reorientates your whole life towards ultimacy, not mere immediacy.

Arguably, one of the most troubling things about our time is the presence of so many mediators, each vying for our attention, each drawing us from one banal concern to another and another and another. This is the essence of the attention economy, which more or less instructs us to believe that everything we are paying attention to is causing us to miss out on something else we should be paying attention to. In the attention economy, everything and everyone can be a rival to everything and everyone else. It’s no wonder so many scandals proliferate, both subtle and vivid. How do you grab the attention of people whose attention is on other things? The answer many people offer is that this is done by appealing to the lowest and basest of human impulses. A high-profile figure commits adultery. An actress undergoes body-modification surgery and self-identifies as a man. Kanye’s latest song causes a stir, and so on.

And in looking at such scandalous things, considering them with an alert contemplative awareness, we might feel superior to those who are being degraded or who are degrading themselves, even as we feel inferior to those invisible rival-mediators who know more than we do about the meaning of such scandals. We feel superior to the bait and the scapegoats of the world, even as we are oblivious to the very hunter whose desire for our capture we are copying. The scandal is both enticing and repellent. Every scandal is a double-bind. Escaping scandal is only possible if, in some mysterious way, all such things are already reconciled and forgiven, and if we are also reconciled and forgiven. It’s easier not to fall into the trap when you notice the hunter who set up the trap; when you see that his desire for you to be his prey is not the desire you want to imitate, after all.

Forgiveness, which offers a profound way of attending to all of reality and not just a way to absolve those who have wronged us, is ultimately the most powerful source of freedom from scandals. It doesn’t surprise me that Jesus, the greatest of all de-scandalisers, made forgiveness central to his philosophy. You are forgiven insofar as you also forgive. You experience freedom in proportion to the freedom you grant others. Love your enemies. Pray for those who want to enslave you. What Jesus demonstrates is by no means a simple dismissal of the harm caused by evil intentions. Forgiveness by no means implies lying about the damage we do to each other and ourselves, nor is it about denying what others have done to us. Rather, it means admitting the brutal truth about our wrongdoing even as we invite the possibility that we all need healing. We all need to be free of intensely rivalrous mimesis. Maybe that’s not a bad way of looking at scandals: they are half-truths that need to be healed by being set in context, where they are often cut down to size or corrected. When you see a scandal, now that you know what to look for, take a moment to recognise it for what it is. See the hunter behind the trap and the bait. Notice that the hunter wants you to emulate his desire to capture you. Then walk away. It is possible to model nonrivalrous desire in such a way that others, even the most predatory among us, follow suit.

It strikes me as significant that the Greek New Testament’s word for forgiveness is áphesis, which comes from the verb aphíēmi, a compound of two elements. Apó means away, and híēmi means to send or to let go. Taken in its most literal form, the word áphesis means to send away or to let go. Isn’t that remarkable? The scandal invites us to take the bait, to reach out and grab hold of something, and it is precisely in doing so that we are imprisoned. As we bind, so we are bound. But here we find that scandal’s opposite is forgiveness, which involves relinquishing control. As we loosen, so we are loosed. Forgiveness is the opposite of grasping. It is the opposite of taking for ourselves what will only rob us. In Russell Hoban’s 1983 novel Pilgermann, the wounded protagonist, having been wounded by a malicious mob, has a vision of Jesus, who says to him, “The only wholeness is in letting go, and I am the letting go.”

Only in letting go can we discover the mediation that transcends obvious oppositions and rivalrous side-taking. It is only in letting go of the false self generated by emulating the desires of hunters, who are in rivalry with flourishing, that the possibility of discovering the true self emerges. However, paradoxes only make sense if, in some way, the clash of opposites does not ultimately mean rivalry but reconciliation. Reconciliation requires that we see beyond the immediately obvious. Even this, I realise, can cause a scandal. “Blessed is the one who is not scandalised by me,” says Jesus in Matthew 11:6. He says this, I think, because sometimes the most scandalous thing to the endlessly scandalised is the possibility that scandals can be rendered impotent.