The paranoid style of American precrime

On the necessity of transcending leftard schizotemporality

In Storm of Steel, his vividly gripping account of his experiences as an officer in the Great War, Ernst Jünger writes about a fellow soldier named Eisen, a plump little man who was always shivering in the trenches. To fight the cold, he knotted a red-chequered handkerchief under his chin and around his helmet. The difference this would have made would have been minimal but he was after the placebo effect. To fight an enemy that might surprise him at any moment, he had a similarly silly, although ultimately more risky, strategy. Eisen was a walking-talking armoury. As Jünger writes, “He liked going around festooned with weapons—apart from his rifle, from which he was inseparable, he wore numerous daggers, pistols, hand-grenades and a torch tucked into his belt. Encountering him in the trench was like suddenly coming upon an Armenian or somesuch.”

Most terrifyingly and hilariously, he had adopted the habit of carrying hand grenades loose in his trouser pockets. But then, soon enough, he was persuaded that this was not the wisest thing to do. One day, feeling the desire to smoke, he dug in his pockets to find his pipe. A pipe feels very different from a hand grenade, so it never occurred to him that putting the two in the same pocket would be a problem. But, on this specific occasion, as he found the pipe, he didn’t realise that the shank and stem of the mouthpiece had found their way into the loop of a hand grenade pin. As he yanked it out, he was horrified to hear the unmistakable click of a pin being pulled from a grenade. That click, Jünger writes, “usually serves as the introduction to a soft hiss, lasting for three seconds, while the priming explosive burns.”

Eisen panicked. He frantically tried to get the grenade out of his pocket to hurl it as far as he could away from him but his unsettled state undid any shot he had of success. Had it not been for the fact that the grenade was a rare dud, he would have been dead. Eisen found himself, as he later admitted to his fellow soldiers, “half paralysed and sweating with fear” but miraculously “restored to life.” Sadly, just a few months later at the battle at Langemarck, he met his end.

The story feels parable-like. It does not mean one thing but many things. At different times and places, you encounter it and see yourself or someone you know in it. You may see it as an analogy for a crisis or a political moment. Arms races have followed the same structure of panicked anticipation causing, or almost causing, self-annihilation. When I first read it, though, I saw it as reflective of a certain populist left-wing rhetorical and political habit. I’ll call it a leftard habit here, assuming that not all leftists are leftards.

Anyway, the leftard habit I mean involves calling anything that anyone in the outgroup agrees with fascist. Not too long ago, the same rhetoric regarded everyone on the political right as alt-right, but that word is now unfashionable and the older accusation of fascist has returned. An extreme and extremely silly example is a July 2023 article from MSNBC about the “far right’s obsession with fitness.” If being healthy is fascistic, is being a fat slob now a left-wing thing? Almost everyone jumped on the bandwagon to mock this ludicrous idea. I particularly liked two headlines from the Babylon Bee: “Obese Man Explains To Doctor He’s Just Fighting Far Right Extremism” and “California Closes For 2 Weeks To Slow The Spread Of Fascism.” This isn’t the first time I’ve encountered the idea that being concerned about your health might be fascist, however, and it’s not the first time I’ve seen something perfectly ordinary being shoehorned into a World War Two container. It seems to me that paranoid rhetoric, of which the everything-you-don’t-like-is-fascist category is just one example, can be better understood as a manifestation of a particular kind of temporality. It reveals, in other words, a particular way of experiencing or relating to time.

Consider Philip K Dick’s 1956 story Minority Report, re-imagined as a 2002 Spielberg film a few decades later. The driving idea of the story is that in some possible future, terrible crimes can be predicted and so also prevented. The police are alerted to what is going to happen and act swiftly and without mercy. But as one character in Dick’s story notices, there is a rather glaring flaw in the whole precrime system. The people arrested have not committed any crime. They have broken no law but are treated as guilty. They claim that they are innocent and, “in a sense, they are innocent.” Real actions are taken on the basis of what is purely imaginary. Real consequences follow a faulty perception and conception of time.

Dick’s story famously aims to call into question the neat sense of inevitability we might want to draw between our present lives and some possible future. This is a fascinating thing to ponder. Turns out, predicting the future is a messy business when we take it too seriously. Predicting a dreaded future creates horrific problems because the driving interpretive heuristic for that dreaded future is inescapably paranoid. Paranoia does awful things. At the moment, although it is by no means alone in being able to transform paranoia into politics, America is the world leader in fear-mongering, as might be noticed simply in the fact that alien sightings are everywhere in America and almost nowhere else in the world. Whatever more plausible explanations are soon abandoned in favour of the most extreme. Whatever reasonable actions one might take are easily swept aside by a flood of panic.

The reality, as Philip Dick wants us to see, is that our anticipations reshape our actions in the present. As soon as his protagonist John Anderton’s name shows up in the precrime system to confirm him as a future murderer, his actions change to ensure that he becomes the very thing he has been predicted to become. A similar idea plays out in miniature in the scene in the first Matrix film between the Oracle and Neo. The Oracle tells Neo not to worry about a certain vase as he walks into a room. He quickly turns to look for the vase and ends up knocking it over. It falls and breaks and Neo apologises. The Oracle reminds Neo that she told him not to worry about it. Then, she says that what’s really going to bother him later is not her powers of prediction but the problem of whether he would have broken the vase if she hadn’t said anything. The implication is this: He wouldn’t have broken it if she’d said nothing. Her prediction caused the future event. A further implication: Neo will be bothered by the problem of whether he would have broken the vase because the Oracle predicts it.

Jean-Pierre Dupuy suggests that what he calls “enlightened doomsaying” would involve warning people of a terrible possibility in the hope that what they predict will not come to pass. But there is a shadow side to this enlightened vaticination, namely that it is precisely the fear of some terrible possible future that such a terrible possible future might become actual for the paranoid person. This is the current plight of American identitarian leftards. By no means do I want to suggest that the problem is a uniquely leftist one but, right now, it is a problem most evident in leftard actions and, by inference, psychology, especially of the kind that is overly narcissistic and possessed by ressentiment and oversocialisation, as well as with the feelings of inferiority that come with such things.

I want to focus here on left-wing populism, which I’m calling leftardism, and a certain rhetorical trend I’ve noticed perpetuated by many on the left. Their rhetoric revolves strongly around preventing what they call “hate.” What is generally feared, it seems, is that reading hateful words in the media, for example, will immediately lead people to commit atrocities in reality, as if words are magical incantations that will turn anyone into a veritable Manchurian Candidate. “Hate speech online can lead to cruelty and violence in real life,” UNESCO tweeted recently. “Get tips for how you can say #NoToHate.” One of the tips they offer on their website is to “React” because, of course, the idea of reflecting is not part of this insipidly flat worldview.

A moment’s reflection reveals that hate is a false metaphysical category in a counterfeit metaphysics composed of two possibilities. On one hand, there is “love.” This is not love as an affirmation of and participation in reality. There is no erotic Neo-Platonic ladder into infinite agapeic wholeness. There is no connection between this love and the love that never fails in St. Paul’s first letter to the Corinthian church. This so-called love is defined by negative freedom, which refuses all prohibitions. This love is not the love that desires someone particular to love but a general, vague mass of nondescript people to (apparently) love. This is the love of humanity at the expense of the love of specific people that Dostoevsky ridicules in The Karamazov Brothers. This is love at the expense of one’s own wholeness, in fact. This love is barely distinguishable from a sort of manic will to power as determined by a strictly pathological psychology of affirmation. This love, akin to lust manifested as a political category, says, “I’m your ally because we conform to the same ideology.” But then, of course, on the other hand, there is “hate.” This is a term applied to anything and everything that would restrict or seem to restrict this negative freedom and confound the ideological pact and allyship. Personal responsibility is out, narcissism is in.

I read the other day about a certain congressman who was convicted in a law court of so-called gender-based political violence because he posted some things on social media that people didn’t like. He had posted “hate.” Whether he hates anyone, in reality, is not the issue. What is true is not the point. The leftard issue is that he doesn’t comply with the ideology. Some of those disgruntled people offended by this “hate” kicked up a fuss about the fact that he referred to a transgender-identifying politician as a “man who self-ascribes as a woman.” Accompanying the conviction was the suggestion that the accused had committed “digital, symbolic, psychological, and sexual violence” for insinuating that someone with the biology of a man is really a man after all.

But what the man said is perfectly tame, even if some found it offensive. He was not calling for the slaughter of unicorns but simply implying that his own perspective sides with a biological reality over a particular social game. But leftards, who I take here to mean precisely those who conform most vehemently to woke vitalism, are extremely worried about this or that infringement of their social game rules by those not playing the game. So much of their rhetoric suggests an absolute state of paranoia against something like the possibility of a future in which so-called sexual minorities will be rounded up and shipped off to concentration camps where they will be exterminated.

Lately, I’ve seen a few mention the idea of a ‘trans genocide.’ This is rhetoric of the most excessive kind. It is meant to stir emotion not to get people to think about what is going on in reality. In general, as here, leftard rhetoric falls into the trap of cascading various premises and deductions without paying even the least attention to reality. One example is how, a few years ago, Oprah, one of the wealthiest people in America, self-identified as one of the marginalised. More recently, a controversy was sparked when Luke Comb’s cover of Tracey Chapman’s song Fast Car rose to the top of the charts. In one viral tweet, it was claimed that this is “bringing up some complicated emotions in fans and singers who know that Chapman, as a queer Black woman, would have an almost zero chance at that achievement herself.” Of course, this is just a lie. Fast Car, as written and sung by Chapman herself, was nominated for three Grammy Awards, including Record of the Year and Song of the Year. She won Best Female Pop Vocal Performance and Best New Artist. And while there’s a lot wrong with any logic and rhetoric like the above, quite apart from the fact that it is dishonest, what I want to note here is how it relates to time. Very simply, time has become a pointillist concern, ahistorical and hysterical. Time is not seen as a narrative or in the light of memory but has been decontextualised. Time has become schizoid.

At this moment in time, the possibility of terror being unleashed on the minorities named by the left seems absolutely absurd to anyone who is even vaguely aware of who runs the show. The culture war has already been won, and not by the right. Conservatism, despite its connection with ancient virtues and values, is widely regarded as a sort of sickness. Western governments generally back the left; every massive corporation in the world does the same; entertainment is so heavily left-wing now that it is almost impossible to find a simple children’s programme that doesn’t in some way promote gender ideology; educational institutions are so jam-packed with identitarian leftists that they were the first to institutionalise cancel culture; the law in so many Western nations and states is left-wing. The right may have its own reasons to be paranoid, as they were back in McCarthy’s time, but now the precrime unit is firmly in the hands of the left.

If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, is it still fascist? Well, from the commonplace leftoid rhetorical position, yes, obviously. That a man can be convicted of a crime of such a scale that it is called “violence” for just saying a few words suggests that what we are dealing with here is not really a crime after all but precisely what Dick calls precrime. As in Dick’s story, within the left-wing camp, “the post-crime punitive system of jails and fines” has been abolished. There are no crimes but there are innumerable criminals. Nothing has happened and boy are people going to pay for it!

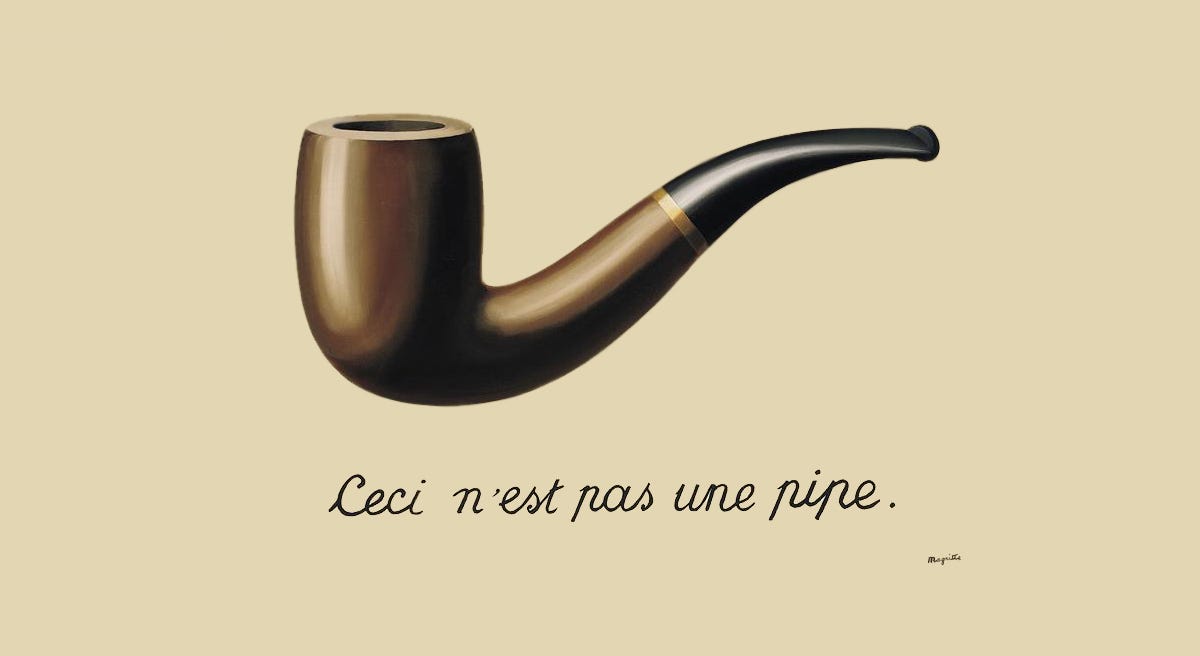

This is where I cannot help but notice the force of the story Jünger tells, which operates at a more familiar level than Dick’s Minority Report. Jünger’s fellow soldier anticipates the very worst; he foresees a battle breaking out at every minute. He, like Anderton in Dick’s story, becomes entirely possessed by his own paranoia. He doesn’t want the enemy to pounce on him and surprise him while he is unprepared. But what does he do in the grip of this paranoia? He reaches for his pipe, that apt symbol of the ceremonial, of leisure and status and, yes, even power. But I want to focus on the fact that it is also a symbol of sheer habit; that is, of a sheer absence of mind. He reaches for his pipe, for some sense of assurance and calm no doubt. It is a familiar thing in the alien and, yes, terrifying world.

But it is the pipe, this very commonplace object of human habit, that causes all the trouble. Its basic function has been considered but nothing else. Its immediate meaning is sensible but no other meaning has been considered. The temporality of the object within a complex world of meaning has been ignored. It has been treated as separate, isolated, and disconnected. The left reaches for its rhetoric and declares even the tamest thing fascist, unaware that by doing so a pin is being pulled out of a grenade, which may not turn out to be a dud. It would not surprise me at all if a new fascism returned precisely because of leftoid paranoia. By increasingly including very normal and harmless forms of human activity within the category of fascism, the left is not combating any enemy but creating it. The enemy is normal itself and, my goodness, is it getting angry.

Including and beyond all of this, I have begun to consider that all politics has, and all political postures have, a sense of temporality. And I have started to wonder what sort of temporality is behind the grenade-hoarding, rhetoric-hurling paranoia of the modern left. What sort of temporality is behind the rhetoric of naming the normal as fascist and talking of all kinds of dismantling as if civilization is somehow standing on solid enough ground to even leverage so much degeneration?

People tend to mistakenly think of time as chronological, as one thing happening after another in a sequence, whether neat or not. But this sequential theory of time is not how we actually experience time. It fails to take into account the fact that our sense of time is psychological before it is, at least in this way, theoretical. In our human, all too human reality, the past is folded up into the future and the future is folded up into the present, and everything is layered in ways that we do not always realise and would struggle to articulate if asked. When I say that all politics has a sense of temporality, therefore, I mean that one’s own psychological sense of time is certainly going to play a significant role in how one conceives of the way we ought to work together.

Here, I must resort to a kind of speculation. I offer this not as a definitive account of current leftard temporality but as a provocation requiring further contemplation. Contemplation is my main aim, as it turns out. My contention is, quite simply, that the new left’s sense of temporality matches something of how Douglas Hofstadter, in Present Shock, describes the experience of digital time. The world becomes possessed by a kind of digiphrenia, a schizoid experience of time as essentially fragmented and broken up. Multiple temporalities co-exist but not harmoniously. The atomised self is at the heart of this, experiencing time as shattered; as if it is comprised entirely of notifications.

The leftard paranoid experience of time is what I want to therefore call schizotemporality. It is a temporality that suggests a breakdown in the relation between thought, emotion, and behaviour, which leads to faulty perceptions, inappropriate actions, irrational feelings, and a withdrawal from reality and personal relationships into fantasy, delusion, and mental fragmentation. One TikTokker recently posted a tearful rant, quoted by @libsoftiktok, against the expectation placed on her to be on time for work. She suffers, she says, from “time blindness.” This nonsense term is, at best, a splinter diagnosis linked to some form of ADHD. It is more likely to be a case of schizotemporality, which manifests as a strong desire to, as this TikTokker says, “dismantle the system.”

Imagine feeling that you are a victim of time. Imagine assuming that feeling like you’re a victim of time is normal. Part of schizotemporality is the degrading of memory and, without memory, the very possibility of conceptualising anything properly is utterly destroyed. Schizotemporality makes identity itself impossible since identity involves continuity. It obsolesces personality since personality relies on an essential coherence with the soul. Both Nietzsche’s last man and Heidegger’s they are schizotemporal manifestations. Schizotemporality ruins any chance of understanding things at an ontological level. It wrecks any hope of retaining your faith in God. Faith takes time, after all. Schizotemporality guarantees paranoia because it blows the possibility of any sensible continuity to smithereens. Reality is experienced as evental, meaning that what happens follows no logic or order and is therefore felt to be a kind of trauma. No wonder even comedy, for instance, has come to be seen through the lense of offense. No wonder literalism dominates discourse. Playful and elastic analogies rely on a temporal fullness that schizo-time won’t allow. Imagination only survives and thrives within a temporality that isn’t schizoid. Schizotemporality begets the everyday linguistic equivalent of bureaucratese. This somewhat explains the catchphraseology and marketing-speak of the average leftard.

Beeps and blips happen all over the place as texts and emails and social media notifications arrive. But schizotemporality is not just a matter of literal notifications. This exaggeratedly disintegrated sense of time is felt even in the constant way that people have begun to hyperlink their own attention into a million false analogies even when they are not plugged into the devil’s electric nervous system. Reality becomes something that you like and subscribe to, or opt out of when it suits you. You can friend it or unfriend it as you like. You can escape into unreality, which is essentially atemporal. You can live in a permanent simulacrum. How does one attain a sense of a continuum in all of this, if this is the only thing you know? Is there any duration in schizotemporality? The simple answer: one doesn’t and there isn’t. Time becomes what Byung-Chul Han, in The Scent of Time, calls “non-time.” Time becomes discontinuous or dyschronous. “The world,” Han writes, “becomes non-timely.”

Whatever has duration comes to seem as empty as a kind of incarnate boredom in a schizotemporal age. Acedia is the vice of schizotemporality, which, if it doesn’t know how to start also doesn’t know how to stop once it gets going. Whatever is full is too full, too rushed, too busy, too much. Time is torn away from people and people are torn away from time. The attention economy is transformed by schizotemporality into a question of what can keep you in a state of absolute splintering as much and as long as possible. Any continuity, any sense of stability, becomes rare, if not inconceivable. How does one narrate life and the world if this is the sense of time that dominates one’s own consciousness? Well, simply, one doesn’t. Schizotemporality is devoid of narrative flow. Things happen but their meaning and connection to the whole is impossible to figure out.

It becomes easy to declare the past entirely full of racism, colonialism, and whateverophobia when one has no sense of time as a complex web of events experienced and created by human beings that cannot be reduced to the simple categories of love or hate, or ally or enemy. It is easy to demand the smooth, a-frictional world of safe spaces in non-time. It is also easy to critique anything, really, the patriarchy or capitalism or heteronormativity, when every notion has been divorced from temporality. Which patriarchy, at which time? Which capitalism and when—and how? And how is heteronormativity bad then when it’s the reason for your very existence? But, of course, existence itself is not a coherent category for the schizotemporal leftard. This partly explains the leftist fight for including death-manufacturing within their ideological paradigm: abortion and euthanasia are high on the leftist list of rights because conception and death are seen as divorced from any existential whole. The leftard attack on biological sex, which is discovered at birth, is, among other things, the result of an allergy to its essentially continuous temporality. The idea that identity was established before you had the chance to presentise it within your schizotemporal framework is deplorable to the leftard.

All of this is to say that leftardism, at this moment in time, in its most woke-capitalist form, mimics and echoes an entirely disjointed sense of temporality. This would make at least some sense given that not only is the past stereotyped but possible future consequences of the current echo of fragmented temporality are generally unthinkable to the left. More equality, more social justice, and more rights are desired. But to what end? Leftism, right now, has no clear telos. Its aims are not really articulated as having any form. They are, by virtue of their discontinuous temporality, entirely formless. The old left, which is now all but dead, at least had utopian dreams. The new left is a frenzy, the perfect breeding ground for the paranoid style of American precrime.

Here is a further speculation. I think all of us, in one way or another, experience this very same sense of temporality, no matter our political leanings. It would be hopelessly naive to assume that schizotemporality is an entirely leftard phenomenon. It seems more universal than that. However, by virtue of some nostalgia for duration or some sense of history and narrativity, not all of us fall into the trap of trying to replicate this broken temporality at every level of existence. It is the political right, today, that notices the need to recover a sense of time and memory and narrative, all of which are necessarily intertwined. But there is no such thing now as a totally unified right. Some on the right are still liberals, yearning for the dawning of liberalism before liberalism started to cause decline. There’s the dissident right and the religious right and others who don’t quite fit into a neat category but remain right-wing. Some want Nietzschean vitalism, others want a return to Christian traditionalism. Some want a mix. All want something other than the catastrophic, anti-normative existential vacuum that is the status quo.

Still, everyone on the right is unified by a sense, felt although not always articulated and not always sufficiently well thought-through, that schizotemporality must be constructively answered somehow. The breakdown in the relation between thought, emotion and behaviour that leads to faulty perceptions, inappropriate actions, irrational feelings, and all that, must be answered with a restoration of thought, emotion and behaviour that leads to truthful perceptions, appropriate actions, rational feelings, and a general movement towards harmony in the world, including harmony with God and the supernatural realm. No doubt, various people on the right will have different ways of doing this, and some on the left may attempt to do this too, although my sense is that they should become a proper revolutionary conservative and should therefore also abandon their leftism before doing this. I am here to suggest, however, that whatever the best approach is, two things are absolutely essential. First, an alternative temporality must be felt through the recovery of deep contemplation and, second, an alternative temporality must be rooted in robust philosophical hermeneutics. Such a twofold approach is necessary if a merely mimetic and polarising differentiation of left and right is to be avoided; that is, if a merely alternate expression of the same schizotemporality is to become manifest.

With regard to the first, it will not do to address our disintegrating sense of temporality merely at a theoretical or intellectual level. This would be like suggesting that the best way to feel fed is to think about food. With regard to the second, it will not do to adopt an approach to history that merely seeks out the most immediate and fleeting resonances without any awareness of how we are filtering the past through present concerns. My sense is that a lot of right-wing vitalists, with their Nietzsche-bro bronze-age aspirations, are still caught up in a hermeneutics of immediacy encouraged by the current dominant temporality. History is not a mere online store with multiple products to be absentmindedly selected on the basis of personal preference. History is a teacher but only to those who will listen very, very well. To those who listen poorly, schizotemporality will still dominate.

A last thought. To listen well to history requires time. Duration. Reflection. Lingering. Slowness. Haste-erasure. It especially requires a recovery of a sense of how we are always living in the past, or at least in its wake; but this means knowing that our present framing of the past may also lead us into error. I’m reminded here of a song by Ben Folds called Smoke. In that song, Folds imagines burning a book, a history of his own life, “Leaf by leaf and page by page.” All the sadness and pain in the story can be hurled away, Folds imagines. The binding can be ripped up and the glue torn up and the whole thing can be thrown onto a blazing fire. Is that not the current temporality? History is there to merely serve the present disdain for history. The machinations of futurists are repeated in a neo-avante-garde disregard for time as a continuum, even if it happens to be a very folded-up and complex continuum.

But then Folds notices that as the book of personal history burns, an analogy for how we might treat everything that has happened as disposable, he simply gets surrounded by the resulting smoke. Smoke gets everywhere. There’s more than enough smoke to choke on. It turns out that forgetting the past does not mean that you are living in the present. We cough and splutter as we realise that no matter how much we seem right now to be living in a fractured temporality and no matter how tempting it is to treat said temporality as a model to be imitated, a rich and inventive and imaginative conservativism, the eternal revolutionary conservatism as suggested by Chesterton in his 1908 book Orthodoxy, would mean not just formulating our ideas differently to create new ideological coordinates. It would mean living, as best as we are able, in and with time. I mean, we need a healthy temporality that transcends schizotemporality. It would mean becoming aware of how our past, the good and the bad of it, informs our present. It would mean becoming aware of how our sense of the future, good and bad, informs our actions right now.

And again, this must be lived and not just thought. Only then, deeply and existentially enriched by the depth of time itself and the recovery of a rich awareness of narrative and memory, could anyone stand any hope of transcending the grip of the paranoid style of American precrime.